No Words, Only a Baton

“The great conductor must not only make his orchestra play, he must make them want to play. He must exalt them, lift them, start their adrenalin pouring, either through cajoling or demanding or raging. But however, he does it, he must make the orchestra love the music as he loves it. It is not so much imposing his will on them like a dictator; it is more like projecting his feelings around him so that they reach the last man in the second violin section.” -Leonard Bernstein

Leaders wear a uniform adorned with medals, or a suit and tie sporting perfectly shined shoes. They share their vision with stirring words. They command followers with speeches and e-mails. But, should they? What if a leader used a stick to express himself? What if his manner to motivate and guide was by poking and picking; slashing and swiping; swinging a stick in powerful arcs and short staccato bursts? What can we learn from an orchestra conductor, communicating with no words and only a baton?

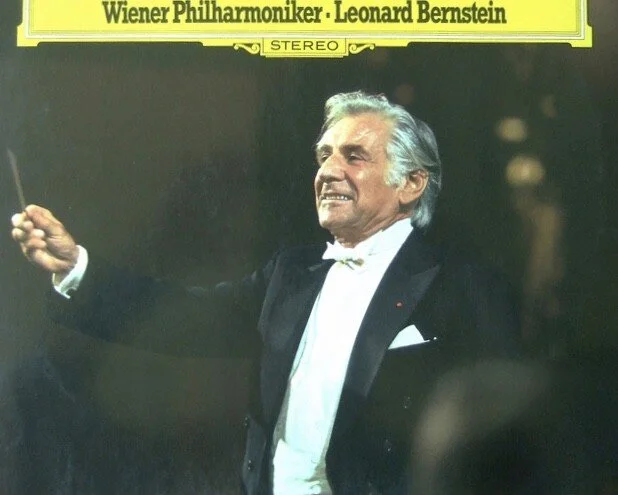

Leonard Bernstein, composer and conductor of West Side Story and other masterworks, was described as “almost impossibly musical, talented, versatile, creative, handsome, energetic, inquisitive, intelligent, charismatic and articulate.” The moments when his leadership mattered most involved no words. Bernstein succeeded because his ego fueled his ambition to excel; however, his interpersonal skills gave him the ability to regulate that ego into being creative and collaborative. When on stage, Bernstein was not dictatorial – “do this, do that.” Instead, he established an environment for his musicians to receive his direction, while collaborating amongst each other. Bernstein’s approach propelled him to become one of the greatest conductors of all time, as he demonstrated with the Vienna Philharmonic, the New York Philharmonic, the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and other premier world orchestras throughout his career.

Leadership emerges from the intersection of a leader, context and follower. In order to successfully fill the leader role, egos must be checked at the door and interpersonal skills must take center stage, as Bernstein famously achieved while conducting. The same leadership framework and ego management must occur in business settings as well, as exemplified by Steve Jobs, the inimitable co-founder and CEO of Apple, Inc.

In an orchestra, a conductor is the leader, one who interprets a composer’s music to ensure a common, unifying musical direction. Bernstein switched from focusing on himself and his ego off-stage, to embodying the educator and responsive, relational leader on-stage. We remember Bernstein – or “Lenny” as he was affectionately known – for both. Similarly, we remember how Jobs started his career as an egomaniac. However, over time Jobs learned the importance of moving his focus to his company and employees. In business, a leader translates the marketplace needs and delivers a strategic vision so that the “followers” work in harmony to meet those needs; it’s no different in an orchestra.

In music, the context is derived from the style of music. If the music is a march, a conductor may use short jerks of a baton; if lyrical melodies, longer, more fluid arm movements are used. Similarly, in a business setting, the context may be the stage of growth of the organization, or the complexity of the competitor landscape. If innovation needs to accelerate, a leader may encourage focus groups or innovation contests; if competition is getting an edge, leaders may scrutinize business processes.

Finally, the followers are the musicians, who abide by the leader’s vision and absorb the context to collectively deliver masterpieces to an audience; not unlike business leaders who guide teams through difficult client problem sets. Through the intersection of the vision of a leader, the context of the environment and the engagement of followers, an organization will hum.

However, leaders must listen to those followers. It is those holding instruments who first recognize the greatest opportunities or biggest risks, and can help steer the orchestra to the beautiful sounds craved by the audience. Similarly, during times of high competition, or changing market requirements, it is the front-line employees of an organization that know the greatest risks and unique ways to adapt and innovate. As front-line employees do the work, it is the orchestra that makes the music, not the leader, nor the conductor. However, if he leads with only his ego, a leader will unwittingly discourage input from his team, and the organization will undoubtedly falter.

In 1945, Bernstein gained awareness of the ego’s self-defeating nature from his manager, Arthur Judson. Bernstein shared that “…[he] told me all conductors become egomaniacs. If that happens, I’ll give up conducting.” Despite having an egotistical tendency outside the concert halls, Bernstein understood that the performance was not about him, but about the musical score in front of him. Similarly, Jobs understood that the success of Apple was not about him, but about communicating the idea of Apple so that his employees could promote its success. Bernstein understood the importance of balancing high, personal ego with the vulnerability and intensity of the musical experience. Jobs combined his ego with passion, focus and a deep emotional connection. With these traits, they were able to drive people to do things they otherwise thought impossible. Both sides of their characters helped craft their legacies.

During his later years, Bernstein’s failing health sometimes required him to use less expressive conducting. Due to his fine leadership in rehearsals, his best orchestras were able to act autonomously and still carry out his artistic vision. Had Bernstein exhibited a dictatorial style when he fell ill conducting, the orchestra may have dwindled to silence, or become a cacophony of sounds. Instead, they knew how to act without his every direction. Similarly, when Jobs first took medical leave, it was questioned if Apple would self-destruct. Learning the import of leading without ego, Jobs was able to ensure that Apple did quite the opposite. Shortly after Jobs began medical leave, Apple’s stocks rose, new products were released, and sales soared.

Bernstein’s leadership style brought musical symphonies to life that reverberated through music halls across the globe. Like with a CEO, a conductor’s work is not so much doing the work, but translating the vision and creating an environment for followers succeed. A conductor’s work is to connect himself with the orchestra, whose performance should wash over the audience like a sonorous, cascading wave. A conductor does this through encouraging an emergent dialogue and connection within the group, for which, his words are the least important aspect. Over the years, Bernstein’s leadership evolved from composer to conductor to teacher and mentor. Encapsulating all of these roles, on his centennial birthday on August 25th, Leonard Bernstein will be forever remembered as one of the most revered conductors among world orchestras, but perhaps more importantly, as a genuine leader of his time. And, his most powerful moments as a leader came without words.